I came to work yesterday morning, absolutely buzzing. I’d just done something momentous (in my mind, at least). It would be a strange boast to many, but when I told my coworker, she congratulated me, her eyes lighting up with genuine pride. I told everyone, some people twice, whether they understood the occasion or not, riding an unbelievable high and wringing it for everything it was worth.

I’d driven my son to school.

No, it was not a particularly long or arduous drive, but it was a drive I wasn’t sure I would ever take.

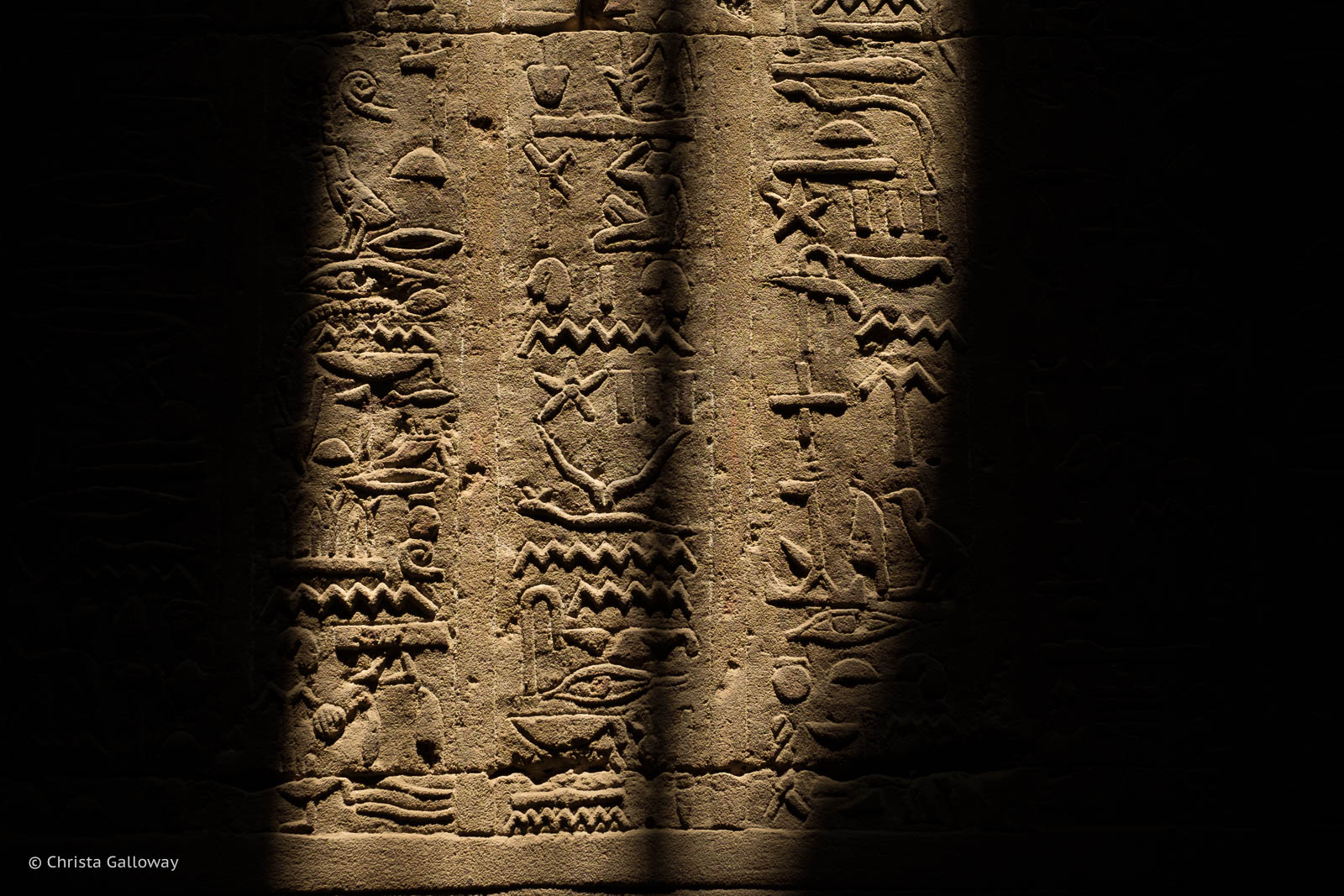

To explain, I’ll need to take you back six years, shortly after we moved to Scotland. We had a tight budget, so we bought an older car, a manual Fiat 500. I hadn’t driven in a few years since we’d been living in Egypt, but I was excited to take the new car out for a spin. I loved driving. I’d worked two jobs during my first year of college to buy my first car, a beautiful blue Dodge Colt. I’d relished the freedom it gave me, often going on a drive alone, just for fun. A couple of decades later, I had a 45-minute commute to work in a manual Toyota Matrix and I once traversed the mountainous west coast of Canada in a Toyota 4Runner, pulling a trailer in the snow. By the time we moved to Scotland, I’d been driving for almost thirty years.

I got behind the wheel of the Fiat, full of confidence.

It did not go well.

Shifting gears with my left hand was surprisingly awkward and I turned on the wipers instead of the turn signal. Meanwhile, driving on the left side of the road somehow meant I constantly drifted towards the curb. Multi-laned roundabouts were foreign to me, and the winding roads did not seem nearly wide enough for two cars to pass each other. These were all obstacles I should have been able to overcome. But this time was different. I was unaware that perimenopause symptoms had begun digging their sharp claws into my brain.

I started having a recurring dream that I was driving a blue van down a hill, but it would not slow down, no matter how hard I slammed my foot on the brake pedal, forcing my to swerve around pedestrians, cars and buildings. I would wake up soaked in sweat, heart pounding.

When I had to drive, I was tense well before I even got in the car. Behind the wheel, my heart would start pounding, my breathing became shallow, and my hands sweaty. While I drove, my brain pelted me with images of everything that could go wrong until my hands shook. Drivers honked at me while I struggled to get the old car into first gear, sending me spiralling into a panic that made me fumble the gears even more or stall the car. Driving became a nightmare.

I went to great lengths to avoid driving. It was my shameful secret. I biked eighteen miles to work and back for the exercise, even in rain and sub-zero temperatures. When my husband and I discussed getting a second car, I insisted one car was all we could afford. There were some truths to these explanations, but really, I didn’t want to face my weakness because it felt like being unable to drive made me less of a person. I hit a low point when the school called because my son was sick, and I had to hire a taxi to fetch him.

We switched to an automatic car, which was an improvement, but on the odd occasion I did drive, it often ended badly: a white-out snowstorm at night or a blown tyre on a main road. During this time, the morning news flashed images of Harry Dunn, a nineteen-year-old boy killed by an American driving on the wrong side of the road, further embedding my worst fear.

What if I killed someone?

One day, my husband injured his ankle, and I had to drive him to the hospital in Aberdeen, a 45-minute drive with three roundabouts. I was tense for the entire drive and had to pry my fingers off the steering wheel when we finally came to a stop. I should have gleaned some confidence back, but somehow, I was convinced the uneventful drive was a fluke, and I made my husband drive back with a twisted ankle.

Over time, I became comfortable enough to drive to work on back roads and made enough trips to quiet the voice in my head that was convinced something horrible would happen. But I didn’t drive beyond that unless I absolutely had to, and if I did, it was a tense experience.

We moved to a little hamlet in a valley, surrounded by countryside, with no shops and no public transportation. It seemed idyllic at the time, but without driving, I began to feel trapped. I remember watching a movie about a woman who was meant to be an absolute mess, her life in shambles, but when she drove herself to the airport for a flight, I envied her.

My bubble shrank and became a dark place. Brain fog had set in, and not only was I making constant mistakes at work, but the setbacks caused me to break down. I cried almost every day. I biked my daily route surrounded by beauty and filled with self-loathing. I was convinced everyone would be better off if I didn’t exist.

My husband became worried. He’d always been my rock, but I’d gone to a place he couldn’t reach. He urged me to get help, but the thought of admitting what was happening would make it real, and doctors were another source of anxiety. The self-loathing intensified. I was blessed with a loving, supportive family, yet I remained mired in gloom. I agreed to seek help if it got worse.

Finally, it was a coworker who helped me change my course. She told me about her journey, consulting a doctor about perimenopause and starting HRT, a process that seemed to give her hope. Hope was a drug I craved, and talking to someone who was experiencing some similar symptoms made me feel less alone.

Finally, I got some help.

I spoke to a doctor, my heart pounding and palms sweaty, spewing my story between shaky breaths. She ordered blood tests and ultimately prescribed me hormone replacement therapy (HRT). I discussed my situation with my female boss. She was very supportive and agreed to give me some time off and shift my duties to more office work.

Over the next few months, I slathered myself with oestrogen gel and took tablets, and I began to feel more clear-headed, less emotionally volatile and more like my old self.

I’ve spoken to several friends with perimenopause now, and while HRT is not for everyone, I think it’s safe to say it changed my life. I still have a good dose of brain fog at work, but most customers are understanding, and when they aren’t, I can handle it. The darkness has mostly lifted. There are still dark moments, but even if I can’t always see the light, I remember the glow of bright days, and I know the dark is temporary. My bubble feels bigger now, if only because the thought of driving doesn’t send me into a panic. In fact, when I get behind the wheel, I feel almost… normal. I’ve made goals for myself, small goals, like driving to the charity shop in the village, or the supermarket outside Aberdeen.

I’m thankful to live in a time where women talk to each other and be honest about our issues. This is one of the reasons I wanted to write this post. If you are going through something like this, please know that you are not alone, and there is help available. I hope you can find someone you trust to talk to.

Which leads me to my unremarkable feat.

Yesterday morning, my son missed his school bus.

“It’s okay,” I said. “I’ll drive you.”

And I did.

—-

Here are some resources I used to learn more about what was happening to me:

NHS Menopause Help and Support

My doctor referred me to Menopause Matters to learn more about symptoms and HRT.